What CBT Really Looks Like: Examples Therapists Use Daily

Rod Mitchell, MSc, MC, Registered Psychologist

Key Highlights

Cognitive behavioral therapy is among the most researched therapy approaches, with proven effectiveness for depression, anxiety, trauma, and many other conditions.

CBT techniques target the thought-feeling-behavior connection, where changing one element shifts the entire pattern through your brain's neural pathways.

Most people notice meaningful changes within 4-6 sessions, with typical treatment lasting 12-16 weeks for lasting skill development and relief.

When clients ask me what cognitive behavioral therapy will be like, they're rarely satisfied with technical descriptions of "identifying cognitive distortions" or "behavioral experiments." What they really want to know is: “What will I actually do in sessions? What does this look like for someone dealing with my specific problem?”

This article walks you through detailed examples of cognitive behavioral therapy in action - from specific techniques like thought records and exposure hierarchies to actual therapy dialogues - so you can understand not just *what* CBT is, but *how* it works in practice and whether it might be right for your situation.

While this guide covers general CBT applications, some conditions benefit from specialized approaches. If you're dealing with OCD, our "Inference-Based CBT Guide" explains a targeted CBT variant designed specifically for obsessive-compulsive patterns.

Table of Contents Hide

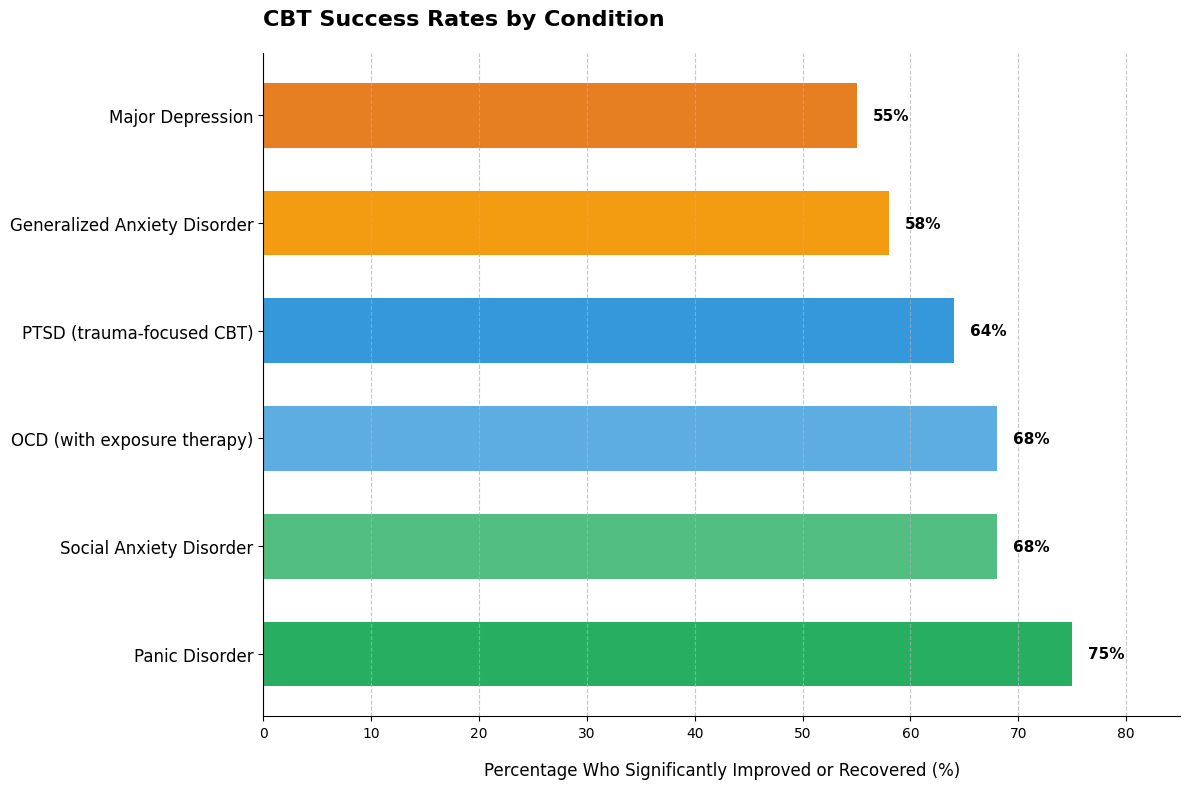

CBT effectiveness varies significantly by condition, from 75% of panic disorder patients becoming panic-free to 55% of depression patients achieving full recovery. All rates exceed medication-alone outcomes (40-50% for most conditions).

Panic disorder responds exceptionally well because panic attacks have clear behavioral triggers that CBT directly targets. Depression shows more modest - but still meaningful - results because it involves multiple complex factors beyond thought patterns.

These rates represent rigorous outcomes (full recovery or no longer meeting diagnostic criteria), not just "feeling a bit better." Based on 12,119 people across 6 major studies (2018-2021). Knowing your condition's baseline success rate helps set realistic expectations.

What Is CBT? Understanding the Core Concepts

CBT operates on a powerful premise: your thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are interconnected, and changing one element shifts the entire pattern.

Picture your morning coffee routine disrupted by a text from your boss requesting an urgent meeting. That single trigger sets off a cascade: anxious thoughts ("I'm getting fired"), physical tension, and avoidance behaviors. Each element amplifies the others unless you interrupt the cycle.

This interconnection isn't random. Throughout your life, you've developed automatic patterns - mental shortcuts your brain uses to process situations quickly. When you walked into your childhood kitchen and smelled cookies baking, you didn't need to think through every step to feel comfort and safety. Your brain linked the smell directly to positive emotion.

The same mechanism creates patterns that don't serve you well. If critical feedback at work repeatedly preceded being dismissed from previous jobs, your brain may now automatically link any critique to job loss - even when the situations differ dramatically.

CBT focuses on present patterns rather than excavating childhood origins. The question isn't "Why did I develop this pattern?" but "How is this pattern operating now, and what can I change?"

Core principles that guide CBT work:

Your interpretations shape your experience more than events themselves

Patterns are learned, which means they can be unlearned or modified

Small changes in thinking or behavior create ripple effects across the entire system

You're an active participant, not a passive recipient of insights

Skills you develop become tools you own permanently

Dr. Stefan Hofmann, director of the Psychotherapy and Emotion Research Laboratory at Boston University, explains: "CBT doesn't just treat symptoms; it fundamentally changes how people process information and regulate emotions."

In my practice, I've observed a consistent pattern. Clients initially struggle to see how their thoughts influence their feelings - it seems like emotions just happen to them.

Then comes the shift. Someone realizes that interpreting their partner's silence as anger creates entirely different feelings than interpreting it as tiredness. That recognition - that they have agency in the process - often marks the beginning of real change.

This collaborative approach differs from therapies where the therapist interprets your experiences for you. In CBT, you and your therapist work as partners to identify patterns, test alternative approaches, and build practical skills you'll use long after therapy ends.

Research extensively supports this approach. Meta-analyses examining hundreds of studies confirm CBT as one of the most effective treatments for depression, anxiety, and numerous other conditions, with benefits that often outlast the therapy itself.

Understanding this foundation prepares you to see how specific CBT techniques - thought records, behavioral experiments, exposure work - put these principles into action with real problems.

Common CBT Techniques Explained

CBT uses specific, teachable techniques that target the thought-feeling-behavior connection.

The six core techniques you'll likely encounter:

Cognitive restructuring and thought records. You learn to identify automatic negative thoughts and examine the evidence for and against them. This might look like: noticing the thought "I'll definitely fail this presentation" and questioning whether you have actual evidence for that prediction versus catastrophic assumption.

Behavioral activation for depression. You schedule specific activities that historically brought satisfaction or accomplishment, even when motivation is absent. This might look like: putting a 10-minute walk on your calendar at 2pm daily, regardless of whether you "feel like it."

Exposure therapy for anxiety and phobias. You gradually face feared situations in a controlled way, building tolerance and reducing avoidance. This might look like: if you've been avoiding phone calls due to anxiety, starting with a 2-minute call to schedule a haircut appointment.

Cognitive defusion. You create mental distance from unhelpful thoughts rather than fighting them. This might look like: instead of thinking "I'm worthless," practicing "I'm having the thought that I'm worthless" - noticing it's a thought, not a fact.

Problem-solving skills training. You break overwhelming problems into manageable steps with specific action plans. This might look like: converting Sunday evening dread about the work week into three concrete actions you can take Monday morning.

Mindfulness integration. You practice observing thoughts and feelings without immediately reacting to them. This might look like: noticing anxiety rising during a difficult conversation and choosing to breathe through it rather than leaving the room.

Research on behavioral activation shows 64% of people with depression experience significant improvement within 8-12 sessions using this technique alone.

"Many clients express relief when we start with behavioral activation. The instruction to simply schedule one meaningful activity feels doable when overthinking has dominated for months." - Dr. Christopher Martell

In my practice, I've found clients often start with thought records because they provide concrete structure. Patterns that felt completely automatic - like immediately assuming criticism in neutral comments - become visible on paper.

That visibility creates the first opening for change. You can't modify a pattern you haven't noticed.

Most people don't use all six techniques. Your therapist will match specific approaches to your particular challenges, adjusting based on what produces results for you.

Real-Life CBT Examples: Seeing Techniques in Action

Understanding CBT techniques matters less than seeing how they work with actual problems. These composite scenarios represent patterns I consistently observe in practice.

Sarah's Social Anxiety: Building an Exposure Hierarchy

Sarah avoided coffee shops for two years after panicking during a crowded morning rush. Her automatic thought: "Everyone will notice I'm anxious and think something's wrong with me."

We built an exposure hierarchy with 10 steps, starting with driving past the coffee shop at a quiet time. Step 5 was entering during off-peak hours and ordering. Step 10 was staying for 20 minutes during morning rush.

After her fifth exposure - ordering during moderate crowd - Sarah reported something shifted. Her anxiety decreased during the situation, not just after. She noticed people focused on their phones, not her trembling hands. Three months later, she met friends there weekly.

Mark's Depression: Activity Scheduling Changes Everything

Mark spent entire weekends in bed, convinced he lacked energy for anything. His automatic thought: "I'll do things when I feel better."

We scheduled three activities weekly: Saturday morning walk (even 10 minutes), Sunday grocery shopping, one weeknight call with his brother. Mark tracked his mood after each activity, not before.

By week three, Mark noticed his mood lifted after activities regardless of how depleted he felt beforehand. The pattern reversed - behavior drove mood change, not the other way around. Within two months, he'd added gym sessions and accepted a dinner invitation.

Lisa's Catastrophic Thinking: Thought Records Reveal Patterns

Lisa's mind spiraled before every work presentation: "I'll forget everything → my boss will think I'm incompetent → I'll get fired." Each prediction felt absolutely certain.

We used thought records to examine evidence. Had she ever completely forgotten a presentation? No. Had anyone been fired for a mediocre presentation at her company? No. What actually happened after her last "terrible" presentation? Her boss thanked her.

After 12 thought record entries, Lisa spontaneously caught herself mid-spiral before a client meeting. She recognized the pattern without prompting - probability overestimation was her signature distortion. That recognition marked a turning point.

James's Anger: Identifying the Trigger-Thought-Response Pattern

James described "instant rage" in his car when someone took his parking spot. By the time he registered what happened, he was yelling. His automatic thought: "That driver disrespected me deliberately."

We slowed down the sequence. Trigger: someone takes spot. Thought: "They saw me waiting and took it anyway." Physical response: face flushing, heart racing. Behavior: honking, yelling. James realized his anger hinged on assuming intentional disrespect.

We practiced alternative interpretations: distracted driver, didn't see him, honest mistake. When James stopped treating every frustration as personal disrespect, his anger episodes dropped from daily to once weekly.

"We've found that clients need 5-7 exposures before they stop focusing on 'surviving' the exercise and start gathering evidence that contradicts their fears. Real learning happens once anxiety drops enough for cognitive processing to occur." - Dr. David A. Clark

In my practice, I've observed a consistent pattern. Clients initially resist exposure work, fearing it will worsen anxiety.

Yet once they experience even small success - Sarah ordering coffee without fleeing - they're ready for the next step. The evidence their body gives them proves more powerful than any reassurance I can provide.

Inside a CBT Session: What It Actually Sounds Like

Most people enter their first CBT session expecting to lie on a couch and talk about their childhood.

The reality surprises them. CBT sessions follow a structured, collaborative format where you and your therapist work as partners examining specific problems.

What clients expect versus what actually happens:

| Common Expectation | Actual CBT Session |

|---|---|

| Free-flowing conversation about whatever comes to mind | Collaborative agenda set in first 5-10 minutes with 2-3 specific topics |

| Therapist analyzes and interprets your experiences | Therapist asks questions that help you examine your own thought patterns |

| Deep exploration of childhood origins | Focus on current patterns and practical skills for present challenges |

| Passive reception of expert wisdom | Active practice of techniques during session with between-session homework |

Research on collaborative agenda-setting shows this structure increases homework completion by 42% compared to therapist-directed approaches.

Dialogue Example 1: Socratic Questioning in Action

Here's what challenging a thought actually sounds like. Client presents with financial anxiety:

Client: "I'm terrible with money. I'll probably end up homeless."

Therapist: "You said you're terrible with money. What's your evidence for that thought?"

Client: "I overspent last month and had to dip into savings."

Therapist: "Having to use savings - does that mean you're terrible with money, or that you have a safety net you created?"

Client: "I guess I never thought about it that way. I do have savings."

Therapist: "What else contradicts the idea that you're terrible with money?"

Client: "Well, I pay my rent on time. And I have been saving, even if I had to use some."

Studies show this questioning approach produces 41% greater cognitive change than direct challenges to thoughts.

Dialogue Example 2: Connecting Thoughts, Feelings, and Behaviors

Watch how a therapist helps someone see the connection between their interpretation and emotional response:

Client: "My manager didn't respond to my email. I feel anxious and I've been avoiding sending follow-up messages."

Therapist: "What thought went through your mind when you didn't get a response?"

Client: "That she's unhappy with my work and ignoring me."

Therapist: "If you believed that thought - that she's unhappy and ignoring you - what emotion would naturally follow?"

Client: "Anxiety. Fear that I'm failing."

Therapist: "And when you feel that anxiety, what do you do?"

Client: "I avoid reaching out because I don't want confirmation that I messed up."

Therapist: "So the interpretation 'she's unhappy with me' leads to anxiety, which leads to avoidance. What's another possible explanation for why she hasn't responded?"

Client: "She could be busy. She usually responds within a few days."

Between-session practice makes skills stick. Your therapist will assign specific homework - thought records, behavioral experiments, or exposure tasks - customized to what you're working on.

Effective homework includes:

Specific implementation details (when, where, how)

Difficulty matched to your current skill level

Clear connection to session insights

Review and troubleshooting at next session start

Each session builds on the last. Your therapist begins by reviewing homework, reinforcing what worked, and problem-solving obstacles before introducing new material.

In my practice, clients often express relief when they realize CBT sessions aren't about lying on a couch being analyzed.

One client told me: "I thought you'd dig into my childhood for months. Instead we made a plan in the first session and I had homework that actually helped." That active, structured approach is what makes CBT work.

Dr. Aaron Beck, founder of cognitive therapy, observed: "Clients consistently tell us they're surprised by how 'normal' and conversational CBT feels compared to their image of lying on a couch. The collaborative detective work, not the therapist's wisdom, creates lasting impact."

CBT Subtypes: Specialized Approaches for Specific Concerns

Standard CBT provides powerful tools, but specialized variations target specific challenges with tailored techniques.

These subtypes aren't entirely different therapies - they build on CBT's core thought-feeling-behavior foundation while adding specific skills for particular struggles.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT): For Intense Emotional Reactions

DBT addresses emotional dysregulation - when feelings arrive suddenly, intensely, and last for hours.

Think of someone whose day collapses after one critical comment, or who experiences rage so overwhelming they can't access rational thought. DBT teaches emotion regulation and distress tolerance skills that standard CBT doesn't emphasize.

Research shows DBT reduces suicide attempts by 50% and psychiatric hospitalizations by 77% for people with borderline personality disorder compared to standard treatment.

Dr. Marsha Linehan, who developed DBT, explains: "For severe emotion dysregulation, teaching acceptance skills before change skills is essential. Standard CBT sometimes fails with borderline personality disorder because it emphasizes change without first validating the person's current emotional reality."

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): For Psychological Inflexibility

ACT helps people who've exhausted themselves trying to control thoughts and feelings.

If you've spent years attempting to eliminate anxiety, stop intrusive thoughts, or force yourself to feel differently - ACT offers a fundamentally different approach. Instead of fighting internal experiences, you learn to have them while still moving toward what matters.

Studies show ACT proves particularly effective for chronic pain and intrusive thoughts, where control attempts often worsen symptoms.

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT): For Depression Relapse Prevention

MBCT targets a specific problem: preventing depression from returning after recovery.

If you've experienced three or more depressive episodes, your brain has created well-worn neural pathways back to depression. MBCT teaches you to notice early warning signs - negative thought patterns, physical tension, withdrawal impulses - without getting pulled into full relapse.

The approach combines standard CBT with meditation practices that create distance from thoughts.

When each subtype typically fits best:

Consider DBT if you:

Experience emotions that feel overwhelming and uncontrollable

Struggle with self-harm urges or suicidal thoughts

Find relationships intensely difficult due to emotional reactivity

Notice emotions shift rapidly and unpredictably

Consider ACT if you:

Feel exhausted from trying to control anxious thoughts

Avoid situations because certain feelings seem intolerable

Lost connection to what matters while managing symptoms

Experience chronic pain or medical conditions with emotional components

Consider MBCT if you:

Have recovered from depression but fear relapse

Notice depressive patterns starting but catch yourself early

Experienced three or more previous depressive episodes

Want skills specifically designed for long-term prevention

In my practice, the appropriate approach often becomes clear within the first few sessions.

If someone describes feeling emotionally hijacked - where anger or fear arrives so fast they can't think - DBT's skills usually resonate immediately. When someone says they're exhausted from battling their own mind, ACT's permission to stop fighting often brings visible relief.

What Conditions Can CBT Effectively Treat?

One of the first questions people ask: "Will CBT actually help with what I'm dealing with?"

Research establishes CBT as a "gold standard" treatment for anxiety and depression, with major organizations including the American Psychological Association and National Institute of Mental Health recommending it as a first-line intervention. But CBT's effectiveness extends far beyond these two conditions.

CBT demonstrates strong evidence for treating:

✓ Depression and mood disorders

Including major depression, persistent depressive disorder, and seasonal patterns. Research shows 50-60% of people achieve significant improvement with CBT.

✓ Anxiety disorders

Panic disorder, generalized anxiety, social anxiety, and specific phobias respond particularly well, with 60-70% experiencing meaningful symptom reduction.

✓ Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Trauma-focused CBT addresses intrusive memories, avoidance patterns, and hypervigilance. Requires specialized training and careful pacing.

✓ Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

Exposure and response prevention - a CBT technique - is considered the most effective psychological treatment for OCD, targeting both obsessions and compulsive behaviors.

✓ Eating disorders

CBT forms the foundation for bulimia and binge eating disorder treatment. Anorexia typically requires multidisciplinary care with CBT as one component.

✓ Substance use and addiction support

CBT helps identify triggers, develop coping strategies, and prevent relapse. Most effective when combined with other recovery supports.

✓ Chronic pain and medical conditions

CBT addresses the psychological aspects of pain, helping people develop coping skills and reduce pain-related disability even when physical symptoms persist.

✓ Life stress and transitions

Career changes, relationship challenges, grief, and adjustment difficulties respond well to CBT's practical, problem-solving approach.

Dr. Stefan Hofmann, director of Boston University's Psychotherapy and Emotion Research Laboratory, explains: "CBT's mechanisms - cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation, exposure - are transdiagnostic. The effectiveness depends less on the diagnostic label and more on how well we can engage these mechanisms for the individual's specific symptom presentation."

In my practice, I've observed that the severity and complexity of symptoms often matter more than the diagnostic category itself.

Someone with moderate depression and strong social support frequently progresses faster than someone with mild anxiety but significant avoidance patterns affecting multiple life areas. The fit between your specific presentation and CBT's approach determines outcomes more than your diagnosis alone.

CBT also supports recovery from conditions not listed here, particularly when adapted by experienced therapists. If your concern isn't mentioned, that doesn't automatically mean CBT won't help - it's worth discussing with a CBT-trained professional.

What to Expect From CBT: Duration, Sessions, and Progress

One of the first questions people ask: "How long will this take?"

Most CBT treatment for anxiety and depression runs 12-16 sessions. Some people need fewer - perhaps 8-10 sessions for a specific phobia. Others benefit from 20+ sessions when dealing with complex trauma or multiple conditions.

Session formats vary based on your needs and circumstances:

Weekly 50-minute sessions work well during active skill-building phases

Biweekly sessions help during maintenance or when practicing skills independently

Intensive formats (multiple sessions weekly) sometimes benefit OCD or severe anxiety

Virtual sessions offer flexibility without compromising effectiveness for most concerns

Research reveals that progress follows a surprising pattern. About 40-50% of your total improvement typically occurs in the first quarter of treatment. Then gains become more gradual - not because therapy stops working, but because you're building lasting skills rather than just reducing crisis symptoms.

This non-linear pattern catches people off guard. You might experience significant relief by session 5, then feel like progress stalls between sessions 8-12. That plateau often precedes breakthrough moments where skills suddenly click into place.

Most people notice initial changes around sessions 4-6. You might catch yourself using a technique without thinking about it, or realize you handled a difficult situation differently than you would have a month ago.

Between-session practice matters as much as session time. Successful CBT clients typically invest 45-60 minutes weekly on homework - thought records, behavioral experiments, or exposure tasks. This isn't busy work; it's how techniques become automatic skills you own.

"The data paint a clear picture - CBT progress is anything but linear. We see rapid early gains, then what clients often perceive as 'stalling out,' followed by consolidation and breakthrough moments." - Dr. Robert DeRubeis, University of Pennsylvania

In my practice, I've observed that progress often feels frustratingly slow until suddenly a shift happens.

You realize you handled your boss's critical email without spiraling, or you attended a social event you'd have avoided two months earlier. These moments - noticing change you didn't consciously create - signal that skills have become part of how you naturally respond.

The timeline matters less than consistent engagement. Someone completing 12 focused sessions with regular practice often achieves more lasting change than someone attending 25 sessions sporadically without between-session work.

When CBT Is Challenging: What You Should Know

CBT helps most people who complete treatment - but "most" doesn't mean "all."

Signs standard CBT may need adaptation:

Homework feels overwhelming despite problem-solving

You feel worse after sessions rather than gradually better

Cognitive challenging feels invalidating, like your feelings don't matter

You notice emotional shutdown when discussing difficult topics

Four sessions in, you see no symptom reduction at all

These patterns don't mean therapy won't work. They signal that your treatment needs customization, not that you're failing.

Research tracking thousands of clients reveals a clear pattern: people showing minimal improvement by session 4 rarely benefit from continuing the same approach unchanged. This doesn't reflect personal failure - it indicates the need for protocol modification.

Trauma history particularly complicates standard CBT. When you've experienced developmental trauma or complex PTSD, techniques like cognitive challenging can feel like repetitions of childhood invalidation. Exposure work without adequate preparation may trigger overwhelming emotional reactions.

Studies show that trauma survivors have significantly higher dropout rates from standard CBT protocols - not because the approach is wrong, but because it requires adaptation. Trauma-informed modifications that prioritize safety and emotion regulation first produce dramatically better outcomes.

Rachel came to therapy after a car accident triggered panic attacks. Standard exposure protocols made her symptoms worse initially. We shifted to building grounding skills first - breathwork, body awareness, creating internal safety. Only after three months of this foundation work did exposure become manageable. That adaptation turned a failing treatment into a successful one.

Sometimes crisis stabilization must come first. If you're experiencing acute suicidal thoughts, active substance dependence, or severe dissociation, jumping into standard CBT rarely works. These situations require immediate safety planning and stabilization before skill-building becomes possible.

Therapeutic fit matters enormously. Research confirms that the relationship between you and your therapist predicts outcomes as much as the specific techniques used. If your therapist's style feels dismissive, overly rigid, or mismatched to your needs, that's valuable information - not evidence that therapy won't work.

Consider a different approach when standard CBT produces no progress after 8-10 sessions despite protocol adjustments, your symptoms consistently worsen rather than improve, or you've tried multiple CBT therapists with similar results. Options include psychodynamic therapy, EMDR for trauma, or medication consultation alongside therapy.

"Many clients labeled as 'resistant' are actually showing us they're not ready for the demands we're placing on them. When we adapt the approach to meet clients where they are, outcomes improve dramatically." - Dr. Henny Westra

In my practice, I've observed that clients who struggle with standard CBT often achieve the most profound changes once we find the right modifications.

Someone needing emotion regulation skills before cognitive work isn't more damaged - they're showing us what sequence their nervous system requires. That clinical sophistication, recognizing when to adapt rather than persist, often makes the difference between treatment failure and success.

Struggling with certain CBT techniques doesn't mean you're doing therapy wrong. It means you're providing information about what you need, and a skilled therapist will use that information to adjust the approach.

Conclusion

You now understand what CBT actually looks like in practice - not abstract theory, but real techniques applied to recognizable problems.

The examples you've seen matter. Sarah's gradual exposure to coffee shops, Mark's scheduled activities despite low motivation, the actual therapy dialogues showing Socratic questioning - these demonstrate how CBT translates from concept to concrete action. This approach teaches specific skills you can practice, measure, and eventually use automatically.

CBT offers evidence-based tools for anxiety, depression, anger, trauma, and life stress. Understanding what happens in sessions - the collaborative agenda-setting, between-session homework, thought records and exposure work - puts you in position to decide whether this approach fits your needs.

If you're ready to start, finding the right therapist matters enormously. Research shows that therapists with specialized CBT training beyond their basic degree produce significantly better outcomes - approximately 25% better than those using CBT without formal certification.

Questions to ask when evaluating CBT therapists:

What specific CBT training have you completed beyond your graduate degree?

Are you certified by the Academy of Cognitive and Behavioral Therapy or equivalent organization?

What percentage of your practice uses CBT as the primary approach?

How do you typically structure treatment for [your specific concern]?

What role does between-session homework play in your approach?

What's your experience treating my particular concern?

Dr. David Clark, Professor of Experimental Psychology at Oxford, states: "The single best predictor of CBT treatment quality is whether the therapist has pursued specialized CBT training and supervision beyond their basic professional degree."

Therapeutic fit matters as much as credentials. If your first therapist doesn't feel right - if sessions feel dismissive, overly rigid, or mismatched to your communication style - that's valuable information, not failure. Trying another therapist is completely normal and often necessary.

In my practice, I've observed something consistent about clients who read detailed examples before starting therapy.

They arrive with realistic expectations about the work involved and clearer questions about how CBT will address their specific situation. That preparation doesn't guarantee easier therapy, but it does support more effective collaboration from session one.

You now have what most articles about CBT don't provide - concrete examples of techniques in action, actual therapy dialogues, and realistic expectations about the process. That clarity about what CBT looks like when it's working puts you in position to make an informed decision about your mental health care.