Canadian Mental Health Statistics 2026: The Latest Facts, Figures, and Trends

Rod Mitchell, MSc, MC, Registered Psychologist

Mental health affects nearly every Canadian family. Understanding the scope of the problem - who's affected, where care falls short, and what's changing - helps us respond with both compassion and practical support.

This page from our counselling clinic in Calgary, AB, compiles 230+ statistics from trusted Canadian sources including CMHA, Statistics Canada, CIHI, and CAMH. Every fact links to its original source. Use the interactive table below to filter by topic, or scroll through the categorized sections for context and clinical perspective.

This information is for educational purposes and isn't a substitute for professional diagnosis or care.

Last updated: January 2026

Table of Contents Show

Canadian Mental Health Statistics

230+ facts from trusted Canadian sources - CMHA, Statistics Canada, CIHI, CAMH, and more. Every statistic links to its original source. Use the filter or search to find what you need. Last updated: January 2026.

youth OR teen, PTSD veteran, cost billion, etc.

| Statistic | Source |

|---|---|

| 1 in 5 Canadians will experience a mental illness in any given year | CMHA |

| By age 40, about 50% of Canadians will have or have had a mental illness | CMHA |

| More than 6.7 million Canadians are living with a mental health problem or illness today | MHCC |

| Canadians reporting "poor" or "fair" mental health tripled from 8.9% in 2019 to 26% in 2021 | CMHA 2024 |

| 18.3% of Canadians aged 15+ met diagnostic criteria for a mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder in 2022 | Statistics Canada |

| 29% of Canadian adults reported a diagnosis of depression, anxiety, or other mental health condition in 2023 (up from 20% in 2016) | CIHI |

| 14% of Canadians will experience major depressive disorder in their lifetime | CMHA |

| 13.3% of Canadians will experience generalized anxiety disorder in their lifetime | CMHA |

| 3.4% of Canadians will experience bipolar disorder in their lifetime | CMHA |

| Prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder doubled from 2.6% in 2012 to 5.2% in 2022 | Statistics Canada |

| Prevalence of major depressive episodes increased from 4.7% in 2012 to 7.6% in 2022 | Statistics Canada |

| 17.4% of Canadians reported moderate to severe symptoms of depression in early 2023 | Statistics Canada |

| 15.3% of Canadians reported moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety in early 2023 | Statistics Canada |

| Social phobia among young women quadrupled from 6.1% in 2002 to 24.7% in 2022 | Statistics Canada |

| About 20% of Canadian youth aged 25 and under experience a mental illness | CMHA |

| Youth rating their mental health as "fair" or "poor" more than doubled from 12% in 2019 to 26% in 2023 | Statistics Canada |

| 33% of young adults aged 18-24 reported moderate to severe symptoms of depression in 2023 | Statistics Canada |

| 25% of young adults aged 18-24 reported moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety in 2023 | Statistics Canada |

| 33% of girls aged 16-21 rated their mental health as "fair" or "poor" in 2023 (vs 19% of boys) | Statistics Canada |

| Generalized anxiety disorder tripled among young women aged 15-24 from 3.8% in 2012 to 11.9% in 2022 | Statistics Canada |

| Major depressive episodes doubled among young women aged 15-24 from 9.0% in 2012 to 18.4% in 2022 | Statistics Canada |

| 57% of young people aged 18-24 with early signs of mental illness said cost was an obstacle to getting services | CMHA 2024 |

| Almost 1 in 4 (23%) hospitalizations of people aged 5-24 were for a mental illness in 2020 | CMHA |

| Rate of children/youth dispensed mood and anxiety medications increased 18% between 2018-19 and 2023-24 | CIHI |

| Suicide is the second leading cause of death among Canadians aged 15-34 | CMHA |

| 15-20% of Canadians aged 15-30 have experienced thoughts of suicide | CMHA |

| Moderate-to-serious distress (anxiety/depression symptoms) climbed from 24% in 2013 to 44% in 2019 to 38% in 2023 among students | PMC |

| Suicidal ideation among students rose from 11% in 2001 to 16% in 2019 and 18% in 2023 | PMC |

| Self-harm among students rose from 15% in 2019 to 19% in 2023 | PMC |

| 38% of Indigenous Peoples reported their mental health was "poor" or "fair" | CMHA 2024 |

| 45.8% of First Nations adults living off reserve reported very good or excellent mental health (vs 61.5% non-Indigenous) | Statistics Canada |

| 47% of First Nations people living off reserve needed mental health care in the past 12 months | Statistics Canada |

| Only 28% of First Nations people who needed and sought mental health care had their needs fully met | Statistics Canada |

| First Nations youth die by suicide about 6 times more often than non-Indigenous youth | CAMH |

| Suicide rates for Inuit youth are about 24 times the national average | CAMH |

| 22.5% of First Nations adults living off reserve have been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder (vs 10.9% non-Indigenous) | Statistics Canada |

| 20.3% of First Nations adults living off reserve have been diagnosed with a mood disorder (vs 9.8% non-Indigenous) | Statistics Canada |

| Indigenous youth face depression and suicide rates 5-7 times higher than non-Indigenous peers | PMC |

| About 4,500-4,850 Canadians die by suicide every year (approximately 12-13 deaths per day) | PHAC |

| Suicide deaths increased 8.6% from 2021 to 2022 | PHAC |

| The suicide rate among men is three times higher than among women | CMHA |

| Women attempt suicide 3-4 times more often than men | CASP |

| 12% of Canadians have thought about suicide in their lifetime | CASP |

| 3.1% of Canadians have attempted suicide in their lifetime | CASP |

| Canada remains one of only two G7 countries without a national suicide prevention strategy | CMHA 2024 |

| Suicide rate for men aged 80+ is 21.5 per 100,000 | CAMH |

| About 8% of Canadian adults reported moderate to severe PTSD symptoms in 2023 | Statistics Canada |

| 10% of Canadian women met criteria for probable PTSD (vs 7% of men) | Statistics Canada |

| 13% of young adults aged 18-24 reported moderate to severe PTSD symptoms (vs 3% of those 65+) | Statistics Canada |

| Lifetime prevalence of PTSD in Canada is estimated at 9.2% | PMC |

| 76% of Canadians have been exposed to at least one traumatic event in their lifetime | PMC |

| 6.8% of Canadians reported having received a diagnosis of PTSD by a health professional | PHAC |

| 29% of those exposed to sexual assault reported moderate to severe PTSD symptoms | Statistics Canada |

| Two-thirds of Canadians have experienced potentially traumatic events in their lives | CBC/StatsCan |

| 500,000 Canadians miss work due to mental illness every week | CPA |

| About 70% of working Canadians report their work experience impacts their mental health | CPA |

| 1 in 4 (24%) working Canadians report experiencing burnout "most of the time" or "always" | MHRC |

| 69% of working Canadians reported experiencing symptoms of burnout in the previous 12 months | Workplace Strategies |

| 21% of employed Canadians report high or very high levels of work-related stress | Statistics Canada |

| 7.5% of employed Canadians took time off due to stress or mental health reasons in the past year | Statistics Canada |

| Canadians miss an average of 2.4 work days per year due to stress or mental health reasons | Statistics Canada |

| Cost of workplace disability leave for mental illness is about double that of physical illness | CAMH |

| Unemployment rates are 70-90% for people with the most severe mental illnesses | CAMH |

| 50% of people with mental health disabilities are employed | CMHA Ottawa |

| 21.6% of Canadians (6 million people) will experience a substance use disorder in their lifetime | CMHA |

| 79% of Canadians reported past 12-month alcohol use in 2023 | Health Canada |

| 32% of Canadians reported past 12-month cannabis use in 2023 | Health Canada |

| 8,049 people died from opioid poisoning in Canada in 2023 (the highest number ever) | CMHA 2024 |

| An average of 21 opioid-related deaths occurred per day in 2023 | Dunham House |

| 92% of opioid overdose deaths in British Columbia involved fentanyl in 2022 | Freedom Addiction |

| Economic cost of substance use in Canada is estimated at $46-48 billion per year | Act for MH |

| Alcohol and tobacco account for over two-thirds of substance use costs | CAMH |

| 67,000 deaths per year are attributable to substance use in Canada | CAMH |

| 2.5 million Canadians with mental health needs reported they weren't getting adequate care | CMHA 2024 |

| 1 in 5 Canadians aged 12+ reported needing mental health care; 45% felt needs were unmet or only partially met | CBC |

| The median wait time for community mental health counselling across Canada is 22-30 days | CIHI |

| 1 in 10 Canadians waited 143 days or more for community mental health counselling | CIHI |

| 34% of Canadians reported counselling needs as the most likely to be unmet | SAGE |

| Among those who met criteria for a mental disorder, only 48.8% talked to a health professional | Statistics Canada |

| Youth aged 15-24 are 8 times more likely to have unmet mental health needs than adults 65+ | IJMentHS |

| Canadians spend approximately $950 million per year on psychologists in private practice | CMHA |

| About 30% of Canadians pay out-of-pocket for mental health care | SAGE |

| Annual economic cost of mental illness in Canada is estimated at over $50 billion per year | CAMH |

| Mental illness costs Canada $20.7 billion annually due to lost labour force participation alone | Conference Board |

| Total mental health expenditure in Canada was $17.1 billion in 2019 | PubMed |

| Cumulative cost of mental illness over 30 years is expected to exceed $2.5 trillion | MHCC |

| Lost productivity from depression costs the economy at least $32.3 billion annually | CBC |

| Lost productivity from anxiety costs the economy $17.3 billion annually | CBC |

| Every dollar spent on mental health returns $4 to $10 to the economy | Act for MH |

| Lost productivity costs $16.6 billion per year due to workers calling in sick for mental health | Workplace Strategies |

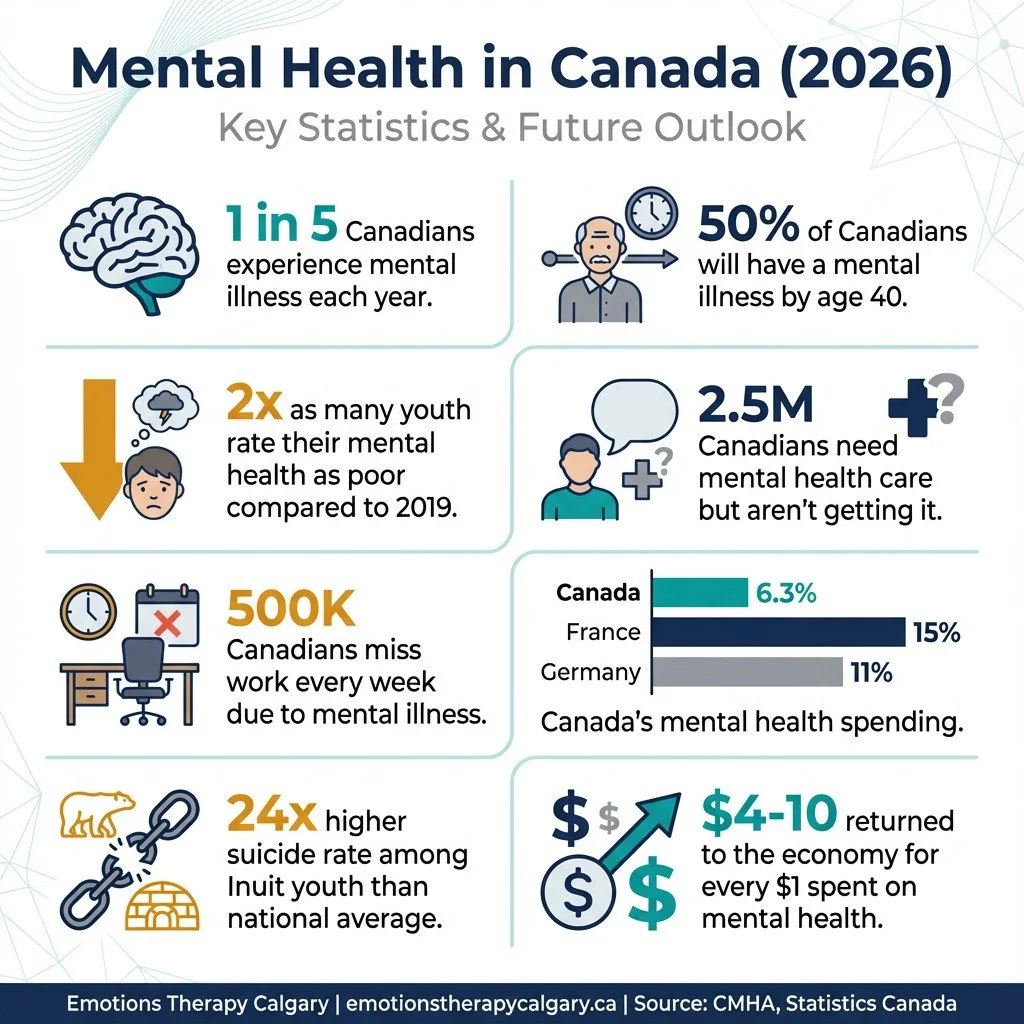

| Provinces and territories spend an average of only 6.3% of health budgets on mental health (should be 12%) | CMHA 2024 |

| Canada spends 6.3% on mental health vs 15% in France, 11% in Germany, 9% in UK and Sweden | CMHA 2024 |

| Mental health spending accounts for 6.4% of total health expenditures in Canada | PubMed |

| Hospital services represent 32% ($5.5 billion) of total mental health spending | PubMed |

| Ontario spends approximately 5.9% of its health budget on mental health (below national average) | CMHA Peel |

| CMHA calls for increasing mental health funding to 12% of healthcare budgets | CMHA 2024 |

| 95% of people with a mental health or substance use disorder have been impacted by stigma in the past 5 years | MHCC |

| 72% of people with a mental health or substance use disorder experience self-stigma | MHCC |

| 40% of participants reported being stigmatized while receiving care in healthcare settings | MHCC |

| 60% of people with mental illness don't seek help for fear of being labelled | CMHA |

| Over one-third of people who received mental health treatment reported discrimination in one or more life domains | PMC |

| 75% of people would be reluctant or refuse to disclose a mental illness to an employer or co-worker | CAMH |

| People are nearly 3 times less likely to disclose a mental illness than a physical one like cancer | CAMH |

| Eating disorders affect about 1 million Canadians (0.3-1% of the population) | CMHA |

| Eating disorders impact women at a rate 10 times that of men | CMHA |

| Eating disorders have the highest rate of mortality of any mental illness | CMHA |

| ED visits and hospitalizations for eating disorders continue to be higher than pre-pandemic levels, particularly for females age 10-17 | CIHI |

| About 1 in 5 Canadian Veterans experience a diagnosed mental health disorder at some time during their lives | VAC |

| 24% of Regular Force veterans reported having a diagnosed mental health condition (depression, PTSD, or anxiety) | PMC |

| PTSD prevalence is 13% among Regular Force veterans and 7% among deployed Reserve Force veterans | PMC |

| Past-year PTSD prevalence in serving CAF personnel increased from 2.8% in 2002 to 5.3% in 2013 | PHAC |

| 44% of CAF members and veterans surveyed experienced symptoms consistent with anxiety or depression between 2002 and 2018 | PHAC |

| 85.6% of CAF members reported exposure to 1 or more traumatic events, with median of 3+ exposures | PMC |

| Nearly 4 in 10 women in the CAF experienced sexual assault | PMC |

| 1 in 4 veterans do not complete residential mental health treatment (high dropout rate) | PHAC |

| 36% of federal inmates are diagnosed with a mental illness at intake | CSC |

| 60% of federal inmates present with a substance use disorder at intake | CSC |

| More than 40% of incoming federal male offenders meet diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder (excluding personality/substance use) | PMC |

| 1 in 7 male federal inmates has major depression or psychosis | PMC |

| Suicide rates are 3-6 times higher in male inmates compared to community populations | PMC |

| 1 in 7 people in custody have attempted suicide | PMC |

| Incarcerated women have higher rates of mental health problems than male inmates, and higher rates of comorbidities | PMC |

| Approximately 1.3 million Canadians identify as 2SLGBTQ+ (4.4% of population aged 15+) | Statistics Canada |

| 2SLGBTQ+ youth are at elevated risk for mental health difficulties and suicidality compared to cisgender heterosexual peers | Statistics Canada |

| 77% of transgender Canadians in Ontario reported they had seriously considered suicide | Made in CA |

| 45% of transgender Canadians in Ontario reported they had attempted suicide | Made in CA |

| Sexual and gender minorities have higher risk of depression, anxiety, and substance use compared to the general population | PMC |

| Among 2SLGBTQ+ youth, 1 in 4 (25%) had experienced suicidal ideation in the past 12 months (vs 5% of cisgender heterosexual youth) | Statistics Canada |

| 56% of 2SLGBTQ+ youth met criteria for a mental health or substance use disorder | PMC |

| 14% of Canadian seniors report having depression, anxiety, or other mental health problems | CIHI |

| 94% of seniors who experience anxiety, depression, or other mental health problems also have chronic physical conditions | CIHI |

| 22% of older adults screened positive for depression in one study | MHCC |

| Only 5% of older adults access health services for mood or anxiety disorders | MHCC |

| 80-90% of older adults living in long-term care have some form of mental disorder | PMC |

| Approximately 50% of older adults in long-term care have a diagnosis of depression | PMC |

| 7.0% of older Canadians (65+) reported having a diagnosed mood disorder; increased from 6.1% in 2015 to 8.5% in 2023 | Statistics Canada |

| Older women (8.3%) are more likely than older men (5.5%) to have a diagnosed mood disorder | Statistics Canada |

| Older adults who self-harm are 67 times more likely to die by suicide than older adults in the general population | CAMH |

| 44.5% of Canadian first responders (police, paramedics, firefighters, 911 operators) screened positive for one or more mental disorders vs 10% of general population | CBC |

| 23.2% of Canadian public safety personnel screened positive for current PTSD | PHAC |

| First responders are twice as likely to experience PTSD than other Canadians | Public Safety Calls |

| Paramedics have a 22% lifetime PTSD rate and suicide rates 5x higher than national average | Public Safety Calls |

| Firefighters have a suicide rate 30% higher than the general population | Public Safety Calls |

| 54.6% of Ontario correctional workers screened positive for one or more mental disorders | Public Safety Calls |

| Suicidal ideation rates among public safety personnel range from 12.5-14.1% | PHAC |

| An estimated 70,000 Canadian first responders have suffered from PTSD in their lifetimes | First Responders First |

| 50% of police officers surveyed rated their perceived stress as high, with 30% having high depressed mood | PMC |

| An estimated 119,574 people experienced homelessness in an emergency shelter in Canada in 2024 | Housing Canada |

| 38% of Canadians who have experienced homelessness report fair or poor mental health (vs 17.3% of general population) | Statistics Canada |

| 31.2% of shelter users identify as Indigenous (vs 5% of population) | Housing Canada |

| 30.2% of shelter users in 2024 met criteria for chronic homelessness (up from 27.6% in 2023) | Housing Canada |

| Approximately 36,058 individuals experienced chronic homelessness in Canada in 2024 | Housing Canada |

| Over 1 in 10 Canadians (11.2%) have experienced some form of homelessness in their lifetime | Statistics Canada |

| Indigenous households (29.5%) are almost 3x as likely to have experienced homelessness compared to the total population | Statistics Canada |

| Homelessness costs approximately $7 billion per year to the Canadian economy | Made in CA |

| It costs $486/day ($177,390/year) to keep a person in a psychiatric hospital vs $72/day ($26,280/year) for housing with community supports | CMHA Ontario |

| Mortality rates among street youth in Montreal are 9x higher for males and 31x higher for females compared to general youth population | PMC |

| Approximately 1 in 6 new mothers experience symptoms of a perinatal mood or anxiety disorder including postpartum depression | PPD.org |

| 23% of mothers who recently gave birth reported feelings consistent with postpartum depression or an anxiety disorder | Statistics Canada |

| COVID-19 pandemic led to a doubling of depression scores in the perinatal population | JOGC |

| 15.5% of women were diagnosed with depression or prescribed antidepressants before becoming pregnant | PHAC |

| 10-15% of new mothers in developed countries are affected by major postpartum depression | PMC |

| Indigenous mothers are 20% more likely to suffer from prenatal and postpartum depression than white mothers | House of Commons |

| Health care professionals identify only 25% of perinatal individuals with postpartum depression | PMC |

| Up to 70% of perinatal women will not seek treatment for mental health disorders | PMC |

| Only 15% of women with a perinatal mental health disorder receive evidence-based care | PMC |

| 42% of perinatal care providers say patients need to wait more than 2 months for mental health services | JOGC |

| 87% of providers believe there are significant barriers to accessing perinatal mental health services | JOGC |

| Suicide is an important direct cause of late maternal death in Alberta and Ontario | JOGC |

| Canada does not have a national strategy for screening and treating perinatal mental health disorders | PMC |

| People in rural and northern Canada are doing worse in mental health, with higher distress particularly in the north | CMHA Peel |

| Rural and remote areas experience acute shortages of qualified mental health professionals and facilities | AWCBC |

| Health status of a population is inversely related to the remoteness of its location | CMHA Ontario |

| Males who live in rural communities are less likely to access mental health supports than men in urban communities | AIDE Canada |

| In Canada, males account for 4 out of 5 deaths by suicide, with rural men at particular risk | AIDE Canada |

| Alberta has only 10.6 psychiatrists per 100,000 people vs 13 per 100,000 nationally | CMHA Edmonton |

| Psychiatrists are concentrated in large urban centres, leaving rural areas underserved | CMHA Peel |

| People receive drastically different care depending on their home province or territory | CMHA Peel |

| Recent immigrants generally have better mental health than Canadian-born population ("healthy immigrant effect") but lose this advantage over time | IRCC |

| Refugees are significantly more likely to report emotional problems and high stress compared to family class immigrants | IRCC |

| Recent immigrants in the lowest income quartile significantly more likely to report high stress and emotional problems | IRCC |

| 5.1% of shelter users in 2023 were refugees and refugee claimants (up from 2.0% in 2022) | Housing Canada |

| Detained migrant children report high rates of emotional distress including separation anxiety, selective mutism, mood and PTSD symptoms | PMC |

| Limited services in languages other than English hampers mental health access for diverse immigrants | PLOS |

Overall Prevalence of Canadian Mental Illness

Mental illness is common in Canada - far more common than most people realize.

1 in 5 Canadians will experience a mental illness in any given year.

By age 40, about 50% of Canadians will have had a mental illness.

More than 6.7 million Canadians are living with a mental health problem today.

18.3% of Canadians aged 15+ met diagnostic criteria for a mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder in 2022.

29% of adults reported a diagnosis of depression, anxiety, or another mental health condition in 2023 - up from 20% in 2016.

The pandemic made things worse. Canadians reporting "poor" or "fair" mental health tripled from 8.9% in 2019 to 26% in 2021. That number has improved slightly but remains well above pre-pandemic levels.

What it means: If you're struggling, you're not an outlier. Mental health conditions are as common as diabetes or heart disease. The difference is we don't always talk about them - which makes people feel more alone than they need to be.

Depression & Anxiety Statistics

Depression and anxiety are the most common mental health conditions in Canada, and both have been rising steadily over the past decade.

14% of Canadians will experience major depressive disorder in their lifetime.

13.3% will experience generalized anxiety disorder.

Prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder doubled from 2.6% in 2012 to 5.2% in 2022.

Major depressive episodes increased from 4.7% to 7.6% over the same period.

In early 2023, 17.4% of Canadians reported moderate to severe depression symptoms, and 15.3% reported moderate to severe anxiety.

The increases are sharpest among young women. Social phobia quadrupled among women aged 15-24 between 2002 and 2022 - from 6.1% to 24.7%.

What it means: These aren't just "bad days." When anxiety or depression persists for weeks and starts interfering with work, relationships, or daily functioning, that's a signal to get support. The good news: both conditions respond well to treatment. In my practice, I regularly see clients make significant progress within months using approaches like CBT, EMDR, or emotion-focused therapy - often without medication, though that's an option too.

Youth Mental Health Statistics

The mental health of Canadian youth has deteriorated sharply over the past decade - and the pandemic accelerated an already troubling trend.

About 20% of Canadians aged 25 and under experience a mental illness.

Youth rating their mental health as "fair" or "poor" more than doubled from 12% in 2019 to 26% in 2023.

1 in 3 young adults aged 18-24 reported moderate to severe depression symptoms in 2023.

1 in 4 reported moderate to severe anxiety.

Girls are hit hardest: 33% of girls aged 16-21 rated their mental health as fair or poor, compared to 19% of boys.

The trend lines are alarming. Generalized anxiety disorder tripled among young women (15-24) between 2012 and 2022. Major depressive episodes doubled in the same group - from 9% to 18.4%.

The healthcare system is responding, but not fast enough. Prescriptions for mood and anxiety medications among children and youth increased 18% between 2018-19 and 2023-24. Almost 1 in 4 hospitalizations of people aged 5-24 are now for mental illness.

And the stakes are high: suicide is the second leading cause of death for Canadians aged 15-34.

What it means: Something fundamental has shifted for young people over the past decade. Social media, academic pressure, economic uncertainty, climate anxiety - the causes are debated, but the trend is undeniable.

What I see clinically is that early intervention makes a significant difference. Teens and young adults often respond quickly to therapy because their patterns aren't as entrenched. The key is catching it early - before a rough patch becomes a years-long struggle. If you're a parent noticing changes in your teen's mood, sleep, or social engagement, don't wait to see if it passes.

Indigenous Mental Health Statistics

Indigenous peoples in Canada face mental health outcomes that reflect generations of systemic trauma - residential schools, forced relocation, and ongoing barriers to culturally appropriate care.

38% of Indigenous peoples reported their mental health as "poor" or "fair."

Only 45.8% of First Nations adults living off reserve reported very good or excellent mental health (compared to 61.5% of non-Indigenous Canadians).

22.5% of First Nations adults living off reserve have been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder - more than double the rate of non-Indigenous Canadians (10.9%).

20.3% have been diagnosed with a mood disorder (vs. 9.8% non-Indigenous).

The suicide statistics are devastating:

First Nations youth die by suicide at 6 times the rate of non-Indigenous youth.

Inuit youth die by suicide at 24 times the national average.

Despite higher need, care is harder to access. 47% of First Nations people living off reserve needed mental health care in the past 12 months - but only 28% of those who sought care had their needs fully met.

What it means: These numbers aren't about individual vulnerability - they're about intergenerational trauma and systemic failure. Healing requires culturally grounded approaches that address historical harm, not just symptom management.

For Indigenous clients seeking support, it's worth looking for practitioners trained in trauma-informed, culturally safe care - or Indigenous-led healing programs that integrate traditional practices with clinical approaches.

Suicide Statistics

Every year, approximately 4,500 to 4,850 Canadians die by suicide. That's 12 to 13 deaths per day.

Suicide deaths increased 8.6% from 2021 to 2022.

The rate among men is 3 times higher than among women.

However, women attempt suicide 3-4 times more often than men.

12% of Canadians have thought about suicide at some point in their lives.

3.1% have attempted suicide.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death for Canadians aged 15-34.

Certain groups face dramatically elevated risk:

First Nations youth: 6x the national rate

Inuit youth: 24x the national rate

Men aged 80+: suicide rate of 21.5 per 100,000

First responders: paramedics have suicide rates 5x higher than the national average

Canada remains one of only two G7 countries without a national suicide prevention strategy.

What it means: The gender paradox in suicide - men die more often, women attempt more often - reflects different patterns of help-seeking and method choice. Men are less likely to reach out and more likely to use lethal means.

If someone you know is talking about wanting to die, feeling like a burden, or feeling trapped - take it seriously. Ask directly: "Are you thinking about suicide?" Asking doesn't plant the idea; it opens the door to conversation.

Our article “Canadian Suicide Statistics (Updated 2026): Rates, Risks, and What Helps” provides more statistics.

PTSD & Trauma Statistics

Trauma is common. PTSD is the clinical disorder that can develop when the brain gets stuck in survival mode after a traumatic event.

About 8% of Canadian adults reported moderate to severe PTSD symptoms in 2023.

10% of Canadian women met criteria for probable PTSD (vs. 7% of men).

Young adults (18-24) are hit hardest: 13% reported moderate to severe PTSD symptoms, compared to just 3% of those 65+.

Lifetime prevalence of PTSD in Canada is estimated at 9.2%.

76% of Canadians have been exposed to at least one traumatic event.

Among those exposed to sexual assault, 29% reported moderate to severe PTSD symptoms.

What it means: Most people who experience trauma don't develop PTSD - but a significant minority do. The symptoms (flashbacks, hypervigilance, avoidance, emotional numbing) often don't appear immediately, and many people don't connect their current struggles to past events.

PTSD is highly treatable. Trauma-focused therapies like EMDR and prolonged exposure have strong evidence bases. In my practice, I've seen clients who've carried trauma symptoms for years experience significant relief within weeks once they start targeted treatment. The key is recognizing that what you're experiencing has a name - and effective solutions exist.

Substance Use & Addiction Statistics

Substance use disorders are mental health conditions - and in Canada, they're reaching crisis levels.

21.6% of Canadians (6 million people) will experience a substance use disorder in their lifetime.

79% of Canadians reported alcohol use in the past year; 32% reported cannabis use.

67,000 deaths per year are attributable to substance use in Canada.

The opioid crisis claimed 8,049 lives in 2023 - the highest ever recorded. That's 21 deaths per day.

Between January 2016 and June 2024, over 49,000 Canadians died from opioid toxicity.

In British Columbia, 92% of opioid deaths involved fentanyl.

The economic toll is staggering: substance use costs Canada $46-48 billion annually. Alcohol and tobacco alone account for two-thirds of that.

What it means: Addiction isn't a character flaw - it's a brain disorder that often develops alongside other mental health conditions like depression, anxiety, or trauma. When substance use and mental health issues overlap, integrated treatment works best. Addressing only one while ignoring the other rarely leads to lasting recovery.

Workplace Mental Health Statistics

Work is where Canadians spend most of their waking hours - and it's taking a toll.

500,000 Canadians miss work due to mental illness every week.

70% of working Canadians say their work experience impacts their mental health.

1 in 4 working Canadians report experiencing burnout "most of the time" or "always."

69% reported burnout symptoms in the past 12 months.

21% of employed Canadians report high or very high work-related stress.

The most common cause? Heavy workloads (affecting 23.7% of workers).

The financial impact on employers is significant: disability leave for mental illness costs about double that of physical illness. And unemployment rates are 70-90% for people with the most severe mental illnesses.

What it means: Workplace mental health isn't just an HR issue - it's a business issue. But from a clinical perspective, the bigger concern is how work stress compounds existing vulnerabilities. I often see clients whose anxiety or depression was manageable until work demands pushed them past their threshold. Setting boundaries, addressing perfectionism, and building recovery time into your week aren't luxuries - they're necessities.

Treatment Access & Barriers

Canada has universal healthcare, but mental health care remains a patchwork of gaps and waitlists.

2.5 million Canadians with mental health needs report they're not getting adequate care.

Among those who need mental health care, 45% say their needs are unmet or only partially met.

The median wait time for community mental health counselling is 22-30 days.

But 1 in 10 Canadians waited 143 days or more - nearly 5 months.

Among people who meet criteria for a mental disorder, only 48.8% have talked to a health professional.

Youth aged 15-24 are 8 times more likely to have unmet mental health needs than adults 65+.

Cost is a major barrier. 57% of young adults with early signs of mental illness said cost prevented them from getting services. About 30% of Canadians pay out-of-pocket for mental health care, spending roughly $950 million per year on private psychologists.

What it means: The access problem has two layers. The public system has long waits and limited options. Private care works faster but costs $150-250+ per session - out of reach for many Canadians.

If you're navigating this system, a few practical notes: check if your employer has an Employee Assistance Program (EAP) - many offer 6-8 free sessions. Look into whether your province has any publicly funded therapy programs (Ontario's IAPT program, for example). And if you're paying privately, ask about sliding scale fees - many therapists offer reduced rates for clients with financial need.

First Responders & Public Safety Personnel Statistics

Police officers, paramedics, firefighters, correctional workers, and 911 dispatchers face mental health challenges at rates far exceeding the general population.

44.5% of Canadian first responders screen positive for one or more mental disorders (compared to 10% of the general population).

23.2% of public safety personnel screen positive for PTSD.

First responders are twice as likely to experience PTSD as other Canadians.

Paramedics have a 22% lifetime PTSD rate and suicide rates 5x higher than the national average.

Firefighters have a suicide rate 30% higher than the general population.

54.6% of Ontario correctional workers screen positive for one or more mental disorders.

An estimated 70,000 Canadian first responders have experienced PTSD in their lifetimes.

What it means: First responders are repeatedly exposed to trauma that most people will never experience - fatal accidents, violence, death, human suffering. The cumulative effect is what we call "operational stress injury."

The culture in many first responder organizations has historically discouraged help-seeking. That's slowly changing, but stigma remains a barrier. If you're a first responder struggling with intrusive memories, hypervigilance, sleep problems, or emotional numbness, know that these are normal responses to abnormal experiences - and they're treatable. Trauma-focused therapies like EMDR are particularly effective for operational stress injuries.

Perinatal & Postpartum Mental Health Statistics

The transition to parenthood is one of life's most significant psychological adjustments - and mental health support during this period is critically lacking.

Approximately 1 in 6 new mothers experience symptoms of a perinatal mood or anxiety disorder.

23% of mothers who recently gave birth reported feelings consistent with postpartum depression or anxiety.

The pandemic doubled depression scores in the perinatal population.

15.5% of women were diagnosed with depression or prescribed antidepressants before becoming pregnant - a major risk factor.

Indigenous mothers are 20% more likely to experience prenatal and postpartum depression than white mothers.

The screening and treatment gaps are alarming:

Healthcare professionals identify only 25% of people with postpartum depression.

Up to 70% of perinatal women won't seek treatment.

Only 15% receive evidence-based care.

42% of providers say patients wait more than 2 months for services.

Suicide is a significant cause of late maternal death in Alberta and Ontario.

Canada has no national strategy for screening and treating perinatal mental health disorders.

What it means: Postpartum depression and anxiety are among the most treatable mental health conditions - when they're caught. The problem is that new parents often dismiss their symptoms as "normal" exhaustion, and healthcare providers don't always screen effectively.

If you're pregnant or postpartum and experiencing persistent sadness, anxiety, intrusive thoughts, difficulty bonding with your baby, or thoughts of self-harm, please reach out. These symptoms aren't a reflection of your parenting abilities - they're medical conditions that respond well to treatment.

Seniors & Older Adults Mental Health Statistics

Mental health in older adults is often overlooked, undertreated, and complicated by physical health conditions.

14% of Canadian seniors report having depression, anxiety, or other mental health problems.

94% of seniors with mental health problems also have chronic physical conditions.

22% of older adults screen positive for depression.

Yet only 5% access health services for mood or anxiety disorders.

In long-term care, 80-90% of residents have some form of mental disorder.

Approximately 50% of long-term care residents have depression.

Mood disorders among seniors are increasing - from 6.1% in 2015 to 8.5% in 2023. Older women (8.3%) are more likely than older men (5.5%) to have a diagnosed mood disorder.

The suicide risk in older men is particularly concerning: men aged 80+ have a suicide rate of 21.5 per 100,000. Older adults who self-harm are 67 times more likely to die by suicide than their peers.

What it means: Depression in older adults often looks different than in younger people - more irritability, physical complaints, and cognitive changes, less overt sadness. It's frequently dismissed as "normal aging" or misattributed to medical conditions.

If you're caring for an aging parent and noticing withdrawal, loss of interest, sleep changes, or cognitive decline, a mental health assessment is worth pursuing. Late-life depression is highly treatable, and addressing it often improves physical health outcomes too.

LGBTQ2S+ Mental Health Statistics

Sexual and gender minorities in Canada face mental health disparities driven by discrimination, minority stress, and barriers to affirming care.

Approximately 1.3 million Canadians (4.4% of the population aged 15+) identify as 2SLGBTQ+.

2SLGBTQ+ youth are at elevated risk for mental health difficulties and suicidality compared to cisgender heterosexual peers.

77% of transgender Canadians in Ontario have seriously considered suicide.

45% have attempted suicide.

Among 2SLGBTQ+ youth, 1 in 4 experienced suicidal ideation in the past year (compared to 5% of cisgender heterosexual youth).

56% of 2SLGBTQ+ youth met criteria for a mental health or substance use disorder.

Sexual and gender minorities have higher rates of depression, anxiety, and substance use across all age groups. They're also more likely to experience homelessness.

What it means: These statistics don't reflect inherent vulnerability - they reflect the cumulative impact of discrimination, family rejection, and systemic barriers to care. Research consistently shows that acceptance, affirming environments, and access to gender-affirming care dramatically improve mental health outcomes.

If you're 2SLGBTQ+ and seeking mental health support, look for providers who explicitly state LGBTQ+ competency. An affirming therapeutic relationship where you don't have to educate your therapist makes a significant difference.

Veterans & Military Mental Health Statistics

Canadian Armed Forces members and veterans carry mental health burdens shaped by operational stress, trauma exposure, and the challenges of transitioning to civilian life.

About 1 in 5 Canadian veterans will experience a diagnosed mental health disorder in their lifetime.

24% of Regular Force veterans have a diagnosed mental health condition (depression, PTSD, or anxiety).

PTSD prevalence is 13% among Regular Force veterans and 7% among deployed Reserve Force veterans.

44% of CAF members and veterans experienced anxiety or depression symptoms between 2002 and 2018.

85.6% of CAF members have been exposed to one or more traumatic events, with a median of 3+ exposures.

Nearly 4 in 10 women in the CAF have experienced sexual assault.

1 in 4 veterans don't complete residential mental health treatment.

Interestingly, 77% of Canadian veterans rate their mental health as good or very good - slightly higher than non-veterans (72%). But among those with diagnosed conditions, 95% also have chronic physical health problems.

What it means: Military service creates unique mental health challenges - not just combat trauma, but also moral injury, military sexual trauma, and the identity disruption of leaving service. Veterans often respond best to providers who understand military culture and don't require extensive explanation of their experiences.

Homelessness & Mental Health Statistics

Mental illness and homelessness exist in a vicious cycle - each making the other worse.

An estimated 119,574 people experienced homelessness in an emergency shelter in Canada in 2024.

Over 1 in 10 Canadians (11.2%) have experienced some form of homelessness in their lifetime.

38% of Canadians who've experienced homelessness report fair or poor mental health (vs. 17.3% of the general population).

31.2% of shelter users identify as Indigenous (compared to 5% of the general population).

30.2% of shelter users in 2024 met criteria for chronic homelessness - up from 27.6% in 2023.

The mortality toll is devastating: homeless men in Toronto have death rates 2.3-8.3 times higher than the general population. For street youth in Montreal, mortality rates are 9x higher for males and 31x higher for females.

And it's expensive: homelessness costs Canada approximately $7 billion per year. Here's the cruel irony: it costs $486/day to keep someone in a psychiatric hospital but only $72/day to provide housing with community mental health supports.

What it means: Housing is healthcare. You can't effectively treat mental illness when someone doesn't know where they'll sleep tonight. The most effective interventions combine stable housing with wraparound mental health and addiction services - what's called "Housing First."

Economic Impact & Funding Gap

Mental illness carries an enormous economic burden - and Canada's investment in mental health care doesn't match the scale of the problem.

The cost of mental illness:

Annual economic cost: over $50 billion

Lost labour force participation alone: $20.7 billion

Lost productivity from depression: $32.3 billion

Lost productivity from anxiety: $17.3 billion

Workers calling in sick for mental health: $16.6 billion

Cumulative cost over 30 years: expected to exceed $2.5 trillion

The funding gap:

Canadian provinces spend an average of only 6.3% of health budgets on mental health.

Compare that to 15% in France, 11% in Germany, and 9% in the UK and Sweden.

CMHA recommends increasing mental health funding to 12% of healthcare budgets.

Ontario spends just 5.9% - below the national average.

The return on investment is clear: every dollar spent on mental health returns $4 to $10 to the economy.

What it means: We're spending billions on the downstream consequences of untreated mental illness - emergency rooms, disability claims, lost productivity, incarceration - while underfunding the upstream solutions that would prevent those costs. The economic case for mental health investment is overwhelming. The political will hasn't caught up.

Mental Health Stigma

Stigma remains one of the biggest barriers to mental health care in Canada - and it comes from everywhere, including the healthcare system itself.

95% of people with a mental health or substance use disorder have been impacted by stigma in the past 5 years.

72% experience self-stigma - internalizing negative beliefs about themselves.

40% report being stigmatized while receiving care in healthcare settings.

60% of people with mental illness don't seek help for fear of being labelled.

75% would be reluctant or refuse to disclose a mental illness to an employer.

People are nearly 3 times less likely to disclose a mental illness than a physical one like cancer.

What it means: Stigma isn't just about public attitudes - it's embedded in workplace policies, insurance practices, healthcare training, and family dynamics. And self-stigma may be the most damaging form: when you internalize the message that needing help makes you weak or broken, you're less likely to seek care and more likely to suffer in silence.

The antidote to stigma is contact - knowing someone with mental illness, hearing their story, seeing their humanity. That's why speaking openly about mental health, when you're comfortable doing so, matters. Every conversation chips away at the shame.

What These Numbers Mean

A few key takeaways from the data:

Mental illness is common. One in five Canadians will experience a mental health condition this year. By age 40, half of us will have had one. If you're struggling, you're not an outlier - you're in the company of millions.

The system is strained. Wait times are long, costs are high, and 2.5 million Canadians aren't getting the care they need. This isn't a personal failure - it's a structural one.

Early intervention matters. Half of lifetime mental illness begins by age 14. The earlier people get support, the better their long-term outcomes. If you're a parent noticing changes in your child, don't wait.

Treatment works. Depression, anxiety, PTSD, and most other mental health conditions respond well to evidence-based treatment. The challenge is accessing it.

Certain groups face elevated risk. Indigenous peoples, 2SLGBTQ+ youth, first responders, veterans, and people experiencing homelessness all face mental health challenges at rates far above the general population. Addressing these disparities requires targeted, culturally appropriate approaches.

We're underinvesting. Canada spends 6.3% of health budgets on mental health - half of what experts recommend. Every dollar invested returns $4-10 to the economy. The math is clear.

Canadian Mental Health Resources

Crisis Lines:

988 - Suicide Crisis Helpline (call or text, 24/7)

Hope for Wellness Helpline - 1-855-242-3310 (Indigenous-specific, available in Cree, Ojibway, Inuktitut)

Kids Help Phone - 1-800-668-6868 (for youth)

Trans Lifeline - 1-877-330-6366

Finding a Therapist:

Psychology Today Canada directory: psychologytoday.com/ca

Canadian Psychological Association: cpa.ca/public/findingapsychologist

Provincial psychology associations maintain referral directories

Provincial Resources:

Most provinces offer some publicly funded mental health services through community health centres or hospitals

Check your province's health authority website for local options

Workplace:

Ask your HR department about Employee Assistance Programs (EAP)

Many EAPs offer 6-8 free counselling sessions

Frequently Asked Questions

Are mental health conditions becoming more common in Canada?

The data suggests yes - particularly for anxiety and depression, and especially among young people. Generalized anxiety disorder doubled between 2012 and 2022. Major depression increased by 60% over the same period. Whether this reflects true increases in mental illness, better detection, reduced stigma leading to more reporting, or some combination remains debated. What's clear is that demand for mental health services is rising faster than capacity.

How long are wait times for mental health care?

It varies widely by location and type of service. The median wait for community mental health counselling is 22-30 days, but 1 in 10 people wait 143 days or more. Wait times for psychiatry can be even longer - sometimes 6-12 months. Private psychologists and therapists typically have shorter waits (days to weeks) but cost $150-250+ per session.

Is mental health care covered by provincial health insurance?

Partially. Psychiatrists are covered because they're physicians. Psychologists, social workers, and counsellors generally aren't - though some provinces have limited programs. Hospital-based mental health services are covered, but community counselling often isn't. Many Canadians rely on employer benefits, EAPs, or pay out of pocket.

When should I seek professional help?

Consider reaching out when symptoms persist for more than two weeks, when they interfere with work, relationships, or daily functioning, or when you're using substances to cope. You don't need to wait for a crisis. Earlier support typically means faster recovery.

Sources

This article draws on data from:

Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) - State of Mental Health in Canada 2024 Report, Fast Facts

Statistics Canada - Mental Health and Access to Care Survey, Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth, Labour Force Survey

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) - Mental Illness and Addiction Statistics

Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) - Child and Youth Mental Health, Access to Care Reports

Public Health Agency of Canada - Suicide Surveillance, Mental Health Infobase

Mental Health Commission of Canada - Anti-Stigma Research, Investing in Mental Health Report

Veterans Affairs Canada - Veteran Mental Health Statistics

Housing, Infrastructure and Communities Canada - Shelter Data Reports

All statistics link to their original sources in the interactive table above.

Last updated: January 2026