Canadian Suicide Statistics 2026: Rates, Risks, and What Helps

Rod Mitchell, MSc, MC, Registered Psychologist

Suicide touches every part of Canadian society. It's the 9th leading cause of death overall and the 2nd leading cause for people aged 15-34. Yet it remains something many of us struggle to talk about - which makes it harder to prevent.

As a psychologist in Calgary, I see how silence around suicide creates barriers. Clients hesitate to mention suicidal thoughts because they fear how I'll react. Families don't know what signs to look for. And the people most at risk often believe they're alone in what they're feeling.

This page compiles 30 key statistics on suicide in Canada - who's affected, how rates differ across groups, and what's working. Every fact links to its original source. The goal isn't just information; it's to help you understand the landscape so you can have better conversations, recognize warning signs earlier, and know what resources exist.

If you're in crisis right now: Call or text 988 - Canada's Suicide Crisis Helpline. Available 24/7, bilingual, and confidential. For Indigenous peoples: Hope for Wellness Helpline at 1-855-242-3310.

Last updated: January 2026

Table of Contents Show

30 Key Canadian Suicide Statistics

| Statistic | Source |

|---|---|

| National Picture | |

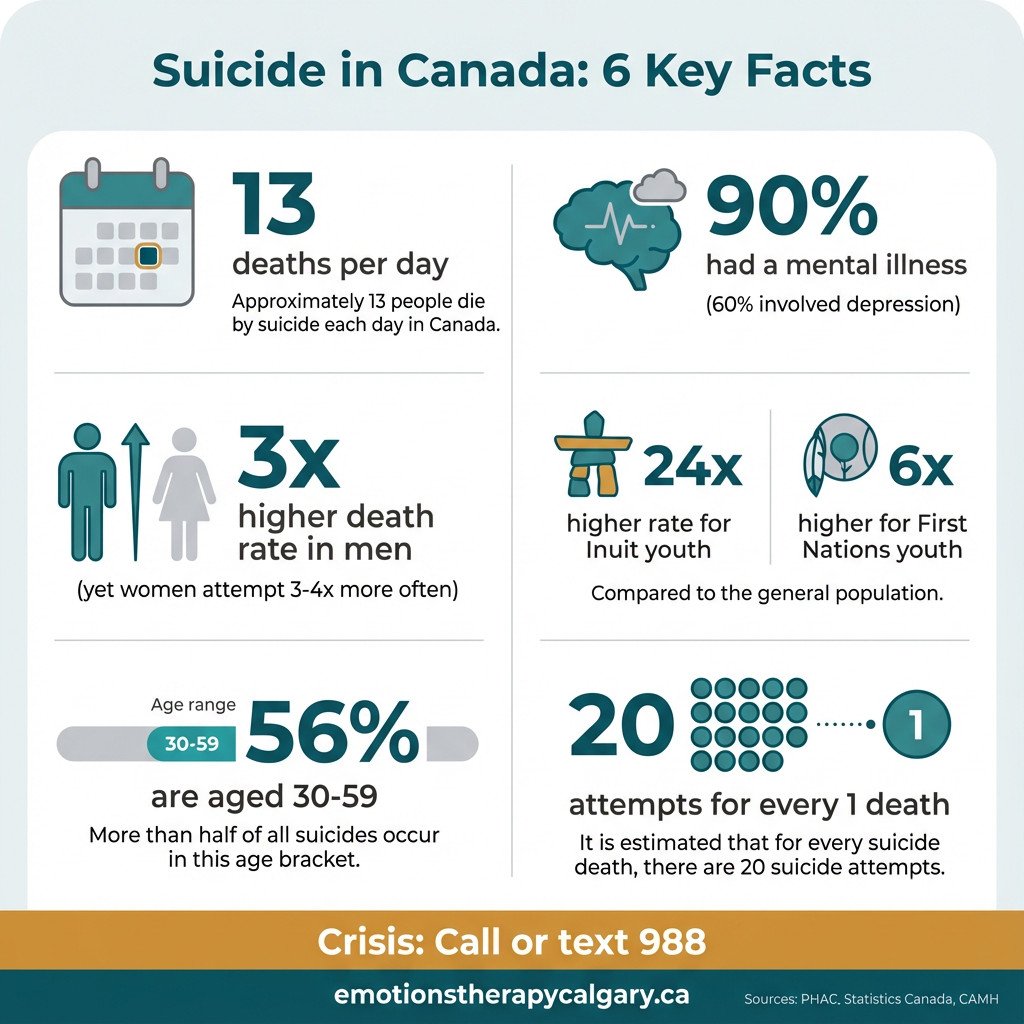

| 4,850 Canadians died by suicide each year. | PHAC |

| That's approximately 13 deaths per day. | PHAC |

| Canada's suicide rate is approximately 10-11 per 100,000 population. | Statistics Canada |

| Suicide is the 9th leading cause of death overall in Canada. | PHAC |

| Suicide is the 2nd leading cause of death for Canadians aged 15-34. | CMHA |

| By Sex | |

| The suicide rate among males is almost 3 times the rate among females. | PHAC |

| Males account for nearly 75% of all suicide deaths. | PHAC |

| Women attempt suicide 3-4 times more often than men. | Statistics Canada |

| For every completed suicide, there are as many as 20 attempts. | Statistics Canada |

| By Age | |

| Middle-aged adults (30-59) account for 56% of suicide deaths. | PHAC |

| Men aged 80+ have a suicide rate of 21.5 per 100,000. | CAMH |

| 12% of Canadians have thought about suicide at some point in their lives. | CAMH |

| Methods | |

| Hanging/suffocation accounts for 54% of all suicides in Canada. | PHAC |

| Poisoning accounts for 25% of suicides; firearms account for 16-18%. | Statistics Canada |

| Among women, 40% of suicides involve poisoning; only 2-3% involve firearms. | PHAC |

| Mental Health Link | |

| More than 90% of people who die by suicide have a mental or addictive disorder. | Statistics Canada |

| Depression is present in approximately 60% of suicide deaths. | Statistics Canada |

| Indigenous Peoples | |

| First Nations youth die by suicide at 6 times the rate of non-Indigenous youth. | CAMH |

| Inuit youth die by suicide at 24 times the national average. | CAMH |

| Nunavut has the highest suicide rate in Canada: 82 per 100,000 (vs. 5.5 in BC). | Statistics Canada |

| Veterans | |

| Canadian veterans are 1.4 to 2 times more likely to die by suicide than the civilian population. | Veterans Affairs Canada |

| Male veterans under age 25 have 2.5 times higher suicide risk than their civilian peers. | Veterans Affairs Canada |

| LGBTQ2S+ | |

| 77% of transgender Canadians have seriously considered suicide. | Trans PULSE |

| 45% of transgender Canadians have attempted suicide. | Trans PULSE |

| First Responders | |

| Paramedics have suicide rates 5 times higher than the national average. | Public Safety Calls |

| Firefighters have a suicide rate 30% higher than the general population. | Public Safety Calls |

| 988 Suicide Crisis Helpline | |

| Canada's 988 helpline has answered 750,000+ calls and texts since launching in November 2023. | CAMH |

| The helpline receives approximately 1,000 calls per day. | CBC News |

| Policy Gap | |

| Canada is one of only 2 G7 countries without a national suicide prevention strategy. | CAMH |

Overall Suicide Rates in Canada

In 2022, 4,850 Canadians died by suicide - approximately 13 deaths per day. That's an 8.6% increase from 2021.

Canada's overall suicide rate sits at about 10-11 per 100,000 population. For context, that's lower than the U.S. (14.2) but higher than many Western European countries. After peaking in the early 1980s, rates declined about 24% by 2017 and have been relatively stable since - though the recent uptick warrants attention.

Perhaps most striking: 12% of Canadians - roughly 1 in 8 - have thought about suicide at some point in their lives. About 3.1% have attempted it.

For every person who dies by suicide, there are as many as 20 attempts. This matters for prevention: most people who attempt suicide don't go on to die by suicide, especially if they receive care afterward. The attempt is often a crisis point that, with the right intervention, becomes a turning point.

What it means: These numbers challenge the assumption that suicide is rare or only affects certain types of people. It's common enough that most Canadians will be touched by it - either personally or through someone they know. That's uncomfortable to acknowledge, but it's also why suicide literacy matters for everyone.

Suicide by Sex: The Gender Paradox

One of the most consistent patterns in suicide data worldwide holds true in Canada: men die by suicide at nearly 3 times the rate of women, accounting for 75% of all suicide deaths.

Yet women attempt suicide 3-4 times more often than men.

This is called the "gender paradox" of suicide. Men use more lethal methods (more on this below), seek help less often, and are more likely to complete suicide on the first attempt. Women attempt more frequently but are more likely to survive.

What it means: From a prevention standpoint, these patterns require different approaches. For men - especially middle-aged men, who represent the bulk of deaths - the focus needs to be on reducing barriers to help-seeking. Men are socialized to "tough it out," to avoid appearing vulnerable, and to solve problems alone. That works until it doesn't.

In my work as a psychologist, I've found that framing therapy as "strategic problem-solving" or "performance optimization" lands better than emotional language. It's not about manipulating anyone - it's about meeting men where they are. The goal is the same: help someone process what they're going through before it reaches crisis level.

For women, the focus is more on safety planning and intervention after attempts - recognizing that a suicide attempt is a serious warning sign but not necessarily a death sentence.

Suicide by Age

Despite assumptions that suicide is primarily a young person's problem, the data tells a different story.

Middle-aged adults (30-59) account for 56% of suicide deaths in Canada. This is the demographic with the highest absolute burden - adults in their prime working years, often with families, careers, and outwardly "successful" lives.

At the other end of the spectrum, men aged 80+ have a suicide rate of 21.5 per 100,000 - among the highest of any group. Older adults, particularly men, face unique risk factors: isolation, chronic illness, loss of independence, bereavement, and fewer perceived reasons to live.

Young people (15-34) have the highest relative burden: suicide is their second leading cause of death, after accidents. But in terms of total numbers, it's the middle-aged demographic that accounts for the most lives lost.

What it means: Suicide prevention efforts that focus only on youth miss where most deaths actually occur. That said, intervening early - during adolescence and young adulthood - can prevent decades of struggle. The ideal approach addresses risk across the lifespan.

Something I've noticed clinically in my practice: the middle-aged demographic often presents differently. They're less likely to talk about "wanting to die" and more likely to express exhaustion, hopelessness about circumstances, or a sense that they're a burden. Listen for phrases like "everyone would be better off without me" or "I just want the pain to stop" - these are indirect ways of expressing suicidal thinking.

Suicide Methods: How Canada Differs from the U.S.

How people attempt suicide matters for prevention - and here, Canada differs significantly from the United States.

In Canada:

Hanging/suffocation accounts for 54% of all suicide deaths - the most common method by far.

Poisoning accounts for about 25%.

Firearms account for only 16-18%.

In the United States, firearms account for 55% of suicide deaths - the dominant method by a wide margin. Canada's stricter gun regulations likely explain the difference.

The methods also vary by sex. Among women:

40% die by poisoning

Only 2-3% by firearms

Among men, firearms are more common (18-20%) but still secondary to hanging.

What it means: Method restriction is one of the most effective suicide prevention strategies. Making lethal means harder to access during a crisis can literally save lives - because most suicidal crises are temporary. Research consistently shows that if someone is prevented from using their intended method, they often don't switch to another; the crisis passes.

This has practical implications. If someone in your life is at risk, reducing access to means - locking up firearms, limiting medication quantities, removing ropes or belts from accessible areas - can create enough time for the crisis to subside or for help to arrive.

The Mental Health Connection

More than 90% of people who die by suicide have a mental health or substance use disorder. Depression alone is present in approximately 60% of suicide deaths.

This doesn't mean mental illness causes suicide - most people with depression never attempt suicide. But untreated mental illness dramatically increases risk, especially when combined with other factors: substance use, chronic pain, relationship breakdown, financial crisis, or access to lethal means.

The relationship also runs the other direction. Suicidal thinking is itself a symptom - of depression, PTSD, borderline personality disorder, and other conditions. When we treat the underlying condition effectively, suicidal ideation typically decreases.

What it means: Suicide prevention and mental health treatment aren't separate issues. They're the same issue viewed from different angles. Improving access to effective mental health care - therapy, medication, crisis support - is suicide prevention.

This is why I find it frustrating when suicide is treated as a separate "awareness" campaign divorced from the broader mental health system. The person at risk of suicide is usually the same person who couldn't get a therapist appointment, couldn't afford treatment, or was discharged from the ER with a pamphlet. Prevention happens upstream.

Indigenous Peoples

Indigenous communities in Canada face suicide rates that reflect generations of systemic harm - residential schools, forced relocation, cultural suppression, and ongoing inequities in housing, healthcare, and economic opportunity.

The numbers are stark:

First Nations youth die by suicide at 6 times the rate of non-Indigenous youth.

Inuit youth die by suicide at 24 times the national average.

Nunavut has the highest suicide rate in Canada: 82 per 100,000 - compared to 5.5 in British Columbia.

These aren't individual mental health problems. They're the predictable outcome of historical trauma compounded across generations.

That said, the picture isn't uniform. 60% of First Nations bands had zero suicides between 2011 and 2016. Research by Michael Chandler and Christopher Lalonde found that communities with greater cultural continuity - those that had control over land, education, health services, and cultural practices - had dramatically lower suicide rates. Self-determination appears to be protective.

What it means: For Indigenous peoples, suicide prevention must be community-led and culturally grounded. Clinical approaches developed for urban, non-Indigenous populations often miss the mark. Healing happens through connection to culture, language, land, and community - not just individual therapy.

If you're Indigenous and seeking support, the Hope for Wellness Helpline (1-855-242-3310) offers culturally safe counselling in English, French, Cree, Ojibway, and Inuktitut. Online chat is available at hopeforwellness.ca.

Veterans

Canadian veterans are 1.4 to 2 times more likely to die by suicide than the civilian population. The risk is highest among younger veterans: male veterans under age 25 have 2.5 times the suicide risk of their civilian peers.

Female veterans also face elevated risk - 1.8 times higher than civilian women - and this elevation persists across all age groups.

The reasons are complex: exposure to trauma and moral injury, difficulty transitioning to civilian life, chronic pain from service-related injuries, and a military culture that can discourage help-seeking. Many veterans also struggle to access care - either because they don't identify as "sick enough" or because the system moves too slowly.

What it means: Veterans often present differently than civilian clients. They may minimize symptoms, use military jargon, or test whether a therapist can handle what they've seen. Building trust takes longer. Approaches like EMDR and prolonged exposure therapy have strong evidence for treating combat-related PTSD, but the therapeutic relationship matters as much as the technique.

If you're a veteran: Veterans Affairs Canada offers mental health services, and you don't need to have a service-related condition to access them. The VAC Assistance Service (1-800-268-7708) provides 24/7 crisis support.

LGBTQ2S+ Communities

LGBTQ2S+ Canadians - particularly transgender individuals and LGBTQ2S+ youth - face dramatically elevated suicide risk.

Among transgender Canadians in Ontario:

77% have seriously considered suicide.

45% have attempted suicide.

Among LGBTQ2S+ youth:

1 in 4 experienced suicidal ideation in the past 12 months - compared to 5% of cisgender heterosexual youth.

56% met criteria for a mental health or substance use disorder.

These numbers aren't about inherent vulnerability. They reflect what happens when people face rejection, discrimination, and violence because of who they are. Family rejection is one of the strongest predictors of suicide attempts among LGBTQ2S+ youth - and conversely, family acceptance is strongly protective.

What it means: For LGBTQ2S+ individuals, finding affirming care matters. A therapist who doesn't understand gender identity, who uses the wrong pronouns, or who subtly pathologizes sexual orientation can do more harm than good. If you're LGBTQ2S+ and seeking support, it's reasonable to ask potential therapists about their experience and approach before committing.

For parents: your response to your child's coming out can be life-saving. Research consistently shows that family acceptance dramatically reduces suicide risk. You don't have to understand everything immediately - but rejection, even subtle rejection, has consequences.

First Responders

The people we rely on in emergencies face their own mental health crisis.

Paramedics have suicide rates 5 times higher than the national average and a 22% lifetime PTSD rate.

Firefighters have a suicide rate 30% higher than the general population.

44.5% of Canadian first responders screen positive for at least one mental disorder - compared to about 10% of the general population.

The reasons are straightforward: repeated exposure to trauma, death, and human suffering. First responders see things most people never encounter once, and they see them routinely. Over time, this accumulates.

The culture compounds the problem. First responders are trained to stay calm, compartmentalize, and "get on with the job." Admitting struggle can feel like weakness - or worse, like a career risk. Many don't seek help until they're in crisis.

What it means: First responders need access to peer support programs, trauma-informed therapy, and workplace cultures that normalize help-seeking. EMDR and other trauma-focused therapies are effective, but the bigger barrier is often getting someone through the door.

If you're a first responder: organizations like Wounded Warriors Canada and the Badge of Life Canada offer peer support specifically for public safety personnel. Your experience is more common than you think.

Canada's 988 Suicide Crisis Helpline

In November 2023, Canada launched 988 - a national three-digit number for suicide crisis support, modeled on the U.S. system.

In its first two years:

The helpline has answered more than 750,000 calls and texts.

It receives approximately 1,000 contacts per day.

Services are delivered through 39 partner centres across Canada.

Support is bilingual, trauma-informed, and culturally appropriate.

This is significant progress. Before 988, reaching crisis support meant remembering a 10-digit number - assuming you knew it existed. A memorable three-digit code reduces friction at the moment when friction is most dangerous.

What it means: If you're ever unsure whether to call, call. 988 isn't just for people actively attempting suicide - it's for anyone experiencing suicidal thoughts, emotional distress, or crisis. The counsellors are trained to help you figure out next steps, whether that's safety planning, connecting to local resources, or just talking through what you're feeling.

You can also text 988. For some people - especially younger Canadians - texting feels more accessible than a phone call.

The Suicide Treatment Gap in Canada

Canada remains one of only 2 G7 countries without a national suicide prevention strategy. (The other is Italy.)

This policy gap has real consequences:

Among people who meet criteria for a mental disorder, only 48.8% have talked to a health professional about it.

2.5 million Canadians with mental health needs report they're not getting adequate care.

The median wait time for community mental health counselling is 22-30 days - and 1 in 10 Canadians wait 143 days or more.

60% of people with mental illness don't seek help for fear of being labelled.

The system is particularly hard on young people. Youth aged 15-24 are 8 times more likely to have unmet mental health needs than adults over 65.

Cost is a major barrier. About 30% of Canadians pay out-of-pocket for mental health care. Psychologists in private practice aren't covered by provincial health insurance, and many people's insurance caps out quickly. 57% of young adults with early signs of mental illness cite cost as an obstacle.

What it means: We have effective treatments for most conditions associated with suicide risk. The problem isn't knowledge - it's access. Until mental health care is treated with the same urgency as physical health care, we'll continue losing people who could have been helped.

What Actually Helps Prevent Suicide

Suicide prevention isn't about a single intervention. It's about layering multiple approaches:

At the system level:

Means restriction: Reducing access to lethal methods during crisis. Canada's firearm regulations likely explain why our suicide rate is lower than the U.S.

988 and crisis services: Making help accessible at the moment of crisis.

Training gatekeepers: Teaching people who interact with at-risk populations (teachers, coaches, doctors, HR staff) to recognize warning signs.

Follow-up after attempts: Research shows that simple interventions - like a caring letter or phone call after a hospital discharge - can reduce repeat attempts.

At the individual level:

Treatment of underlying conditions: Effective therapy and/or medication for depression, PTSD, substance use, and other conditions.

Safety planning: A written plan developed with a clinician that identifies warning signs, coping strategies, reasons for living, and people to contact in crisis.

Connectedness: Social support is consistently protective. Loneliness is consistently a risk factor.

What doesn't help:

Telling someone to "just think positive" or "be grateful for what you have."

Avoiding the topic because you're afraid of "planting ideas." (Research shows that asking directly about suicide doesn't increase risk - it often provides relief.)

Treating a suicide attempt as manipulative or attention-seeking. Even if someone's attempt wasn't "serious," the pain behind it is real.

How to Help Someone at Risk of Suicide

If you're worried about someone, here's what to do:

Ask directly. "Are you thinking about suicide?" isn't going to put the idea in someone's head. It's going to open a door they may have been afraid to open themselves.

Listen without judgment. You don't need to fix anything. Just being present and taking them seriously matters more than having the right words.

Don't leave them alone if they're in immediate danger. Stay with them until help arrives.

Help them connect to support. That might mean calling 988 together, driving them to an ER, or helping them book an appointment with a therapist.

Follow up. After the crisis passes, check in. One of the highest-risk periods is right after someone is discharged from hospital. A simple "I've been thinking about you" text can matter more than you'd expect.

Canadian Resources & Crisis Support

Crisis Lines:

988 – Suicide Crisis Helpline (call or text, 24/7, bilingual)

Hope for Wellness Helpline – 1-855-242-3310 (for Indigenous peoples, available in Cree, Ojibway, Inuktitut)

Trans Lifeline – 1-877-330-6366

Kids Help Phone – 1-800-668-6868 (for youth)

For Veterans:

VAC Assistance Service – 1-800-268-7708

For First Responders:

Badge of Life Canada – badgeoflifecanada.org

Wounded Warriors Canada – woundedwarriors.ca

Finding a Therapist:

Psychology Today Canada directory: psychologytoday.com/ca

Canadian Psychological Association: cpa.ca/public/findingapsychologist

Frequently Asked Questions

Is suicide preventable?

In many cases, yes. Suicide usually occurs at the intersection of a mental health condition, a crisis, and access to means. Intervening at any of these points can save a life. Most people who survive a suicide attempt don't go on to die by suicide - especially if they receive appropriate care afterward.

Does talking about suicide make it more likely?

No. Research consistently shows that asking about suicide doesn't increase risk. For many people, being asked directly provides relief - it signals that someone cares and that it's okay to talk about what they're experiencing.

What are warning signs?

Common warning signs include: talking about wanting to die or being a burden, withdrawing from friends and activities, giving away possessions, increased substance use, dramatic mood changes, and researching methods. Any previous suicide attempt is a significant risk factor.

Why is the male suicide rate so much higher?

Men use more lethal methods, seek help less often, and face social expectations that discourage emotional expression. Prevention efforts targeting men need to account for these realities - meeting men where they are rather than expecting them to adopt traditionally "feminine" help-seeking behaviours.

How can I support someone who has lost a family member to suicide?

Be present without trying to explain or rationalize what happened. Avoid clichés like "they're in a better place." Let them talk about the person who died - including happy memories. Grief after suicide is often complicated by guilt, anger, and unanswered questions. Professional support from a therapist experienced in grief and bereavement can help.

Final Thoughts

Suicide is preventable - not in every case, but in many. The path from suicidal ideation to death usually involves multiple points where intervention could change the outcome: a conversation, a treatment, a moment of connection, a barrier to means.

The statistics in this article aren't just numbers. Each one represents someone's child, parent, partner, or friend. And behind the completed suicides are many more Canadians living with suicidal thoughts - often in silence, often convinced they're alone.

If you're struggling, please reach out. Call 988. Tell someone. The crisis you're in won't last forever, even if it feels that way right now.

And if you're not struggling but know someone who might be - ask them. Your willingness to have an uncomfortable conversation might be the thing that keeps them here.

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. If you're experiencing a mental health emergency, contact 988 or go to your nearest emergency department.